BALDWIN LOCOMOTIVES |

15 |

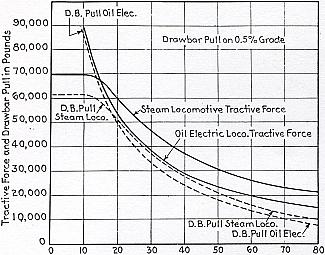

and Drawbar Pull on a 0.5 Per Cent Grade of a 4-8-4 Type Steam Locomotive and a Diesel-Elec- tric Locomotive. live force curve of a better Diesel locomotive than has yet been built. We designed it, but nobody yet has come forward to pay $400,000 or $500,000 which it would cost to build it. This Diesel locomotive has the advantage of two 1975 horsepower engines that weigh only about IS1/^ pounds per horsepower. It has the advantage of special and expensive electrical and mechanical equipment designed to overcome, as far as possible, that characteristic loss at speed of power delivered at the rim of the wheel. But notwithstanding all these things you see that at 80 miles an hour this Diesel locomotive has hardly 15 per cent of its original tractive force left. When, on the other hand, we turn to the tractive force curve of the Northern Pacific 4-8-4 which we built last year, you will note that it has a tractive force at starting of only 70,000 Ibs. But at 80 miles an hour it still has nearly one-third of its original tractive force; and in all the working speeds from 30 miles an hour up it has a constant excess of approximately 8,000 Ibs. of tractive force. And lastly, note that this steam locomotive, which gives a better tractive force curve at all working road speeds, would be reasonably priced at not more than one-third of what it would cost to build the Diesel locomotive with which it is compared. The dotted lines give you the drawbar pull |

of these two locomotives on an 0.5% grade. Even here where the Diesel locomotive has the advantage of greater horsepower at lower speeds, you will note that the drawbar pull of the steam locomotive crosses the Diesel at about 18 miles an hour and above that speed the steam locomotive has about 3,000 Ibs. of drawbar pull more than the Diesel.

Before I let this slide go off, however, let me point out that this tractive force curve brings out the one place in which the Diesel locomotive has a substantial advantage, and that is in its tractive force at low speed. Of course, that is the reason why Diesel power so far has been mainly applied to switching. But the lower the speeds at which the Diesel locomotive is worked, the greater is its advantage. So far as I know, we are the only locomotive manufacturers in the country trying to sell Diesel locomotives for steady drilling over the hump in big classification yards. But by the same token a comparison of these two tractive force curves should be conclusive as to the undesirability of the Diesel as a road locomotive.

Therefore, the field of probable profitable application of the Diesel locomotive is pretty generally indicated at work speeds not exceeding 10 miles an hour. There are many places where such locomotives can show a distinct economy notwithstanding the fact that even Diesel switching locomotives, with none of the expensive elements of the Diesel locomotive which I just showed you, cost approximately twice as much as comparable steam locomotives. But in drilling over the hump of a classification yard; in switching into and out of electrified areas; in protecting the service at outlying points, permitting the doing away with round-house facilities; and in other exceptional places, particularly where one locomotive can be made to do the work of two or three different types, the Diesel can show a return.

But in finding these places it is essential that we keep our feet on the ground all the time. For instance, at the moment, with Diesel oil at 5 cents a gallon, the higher thermal efficiency |